It’s about access! How access to libraries underpins literacy

Dr. Stewart Savard

Teacher-Librarian, Courtenay Middle School

Courtenay, B.C.

Issue Contents

______________________________________________________

To paraphrase Bill Clinton: “It’s about access, stupid!”i This is a critical finding in several international reviews of reading achievement. Students who access and use libraries and their contents – both librarians and books – outperform those students who rarely or never use libraries. Research also clearly demonstrates that students with books in their homes do better on standardized achievement test than their peers with few, or no, books at home. Literacy instruction is a critical element in learning to read, but access to reading material is the key to the continued use of the reading skills learned that results in achievement.

Librarians know that access is critical, but sometimes find it hard to get the message across to decision-makers. Deeply held beliefs may not have the same impact, in the decision-making process, when budgets are evolving, that achievement results can. These results are on the side of maintaining, or even increasing, student access to libraries and librarians.

An Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) study, in 2001, of student achievement, at age 15, demonstrates the clear benefit provided by access. Students who used libraries more often did better than their peers who either did not use a library (or possibly did not have access to one). Purposeful use, for both study and leisure reading, is a factor of access. You cannot effectively use what you do not have access to. Table 1 demonstrates that library use is linked to a significant difference in student achievement in both Reading and Science.

Access and purposeful usage compliment each other in healthy libraries. A student can have access to books and magazines for recreational reading, for example, but without expectations being placed on their usage, by their teacher – who is directing their tasks and by a teacher- librarian – who understands the curriculum and is actively developing a collection to support instruction needs, then access alone will never unlock a student’s full potential.

Time spend reading is a function of access (either through school or public libraries or as a result of a family having the financial resources needed to buy books). The 2006 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) examined the reading achievement of Grade Four students (Mullis, Martin et al. 2007). Generally, students who read more did better in terms of reading, mathematics, and science: all key components in a competitive society. Table 2 (below) shows this difference in terms of Reading achievement.

Table 2 may, in a fashion unexpected by the creators of the 2006 study, demonstrate the difference between access and purposeful use. Students, reading more than two hours a day did less well than their peers who, perhaps, used their time in a more directed fashion. Perhaps the first group needed to put down their reading and complete their homework?

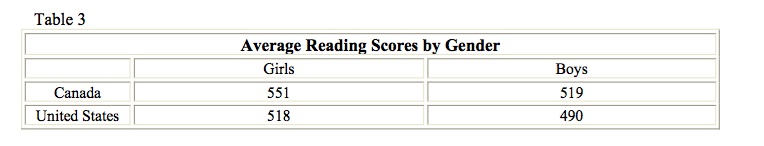

The 2006 PIRL study (Table 3 below) also highlighted the difference in reading scores between girls and boys in Canada and the United States. This finding is troubling in a healthy society. Boys must be as literate as girls for a society to be healthy.

PIRLS does not compare achievement with access, usage, and gender. These might be an interesting research questions. If, as it seems superficially possible to conclude, boys don’t read as much as girls and if this causes part of the gap in achievement, then a piece of the solution must be to transform what libraries contain that is of interest, or relevant, to boys and find ways to have them use their school libraries more often. The 2006 PIRLS also failed to ask about access and usage of school libraries as functions of achievement. The study conflated school and classroom libraries (seemingly assuming that classroom libraries are some kind of adequate subsets of the non-fiction and fiction collections found in school libraries) and sets the entry threshold for “school libraries” as having as few as 500 books.

Access to books at home was directly linked to achievement of grade four students in the 2006 study. While the resource/access question was not reported for respondents from the United States, Canadian students with a significant number of books at home, either because of economic resources, or cultural traditions, outperformed their peers with fewer books at home. The same achievement gap can be found in the international numbers which report the achievement of students in all of the countries participating in this study. Students without books at home need access to them in their school libraries. Healthy school libraries become even more important for students disadvantaged, for whatever reasons, by access to books at home.

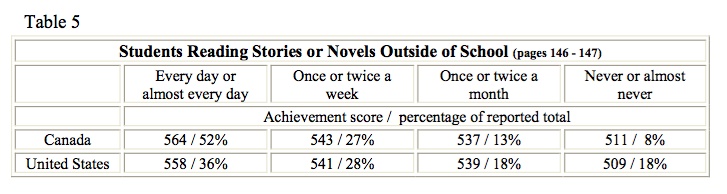

PIRLS 2006 asked students about how much they read. Students who read stories or novels “outside of school” showed a clear difference in terms of their achievement (Mullis, Martin et al. 2007).

The results found in table 5 seem to suggest that there is equal access to reading material. If access isn’t equal, then the lower scores might be raised by providing more opportunities to students and by providing more, and better, school libraries.

Students in grade four generally have some control over what they read outside of school: albeit a lack of exposure to some genre places limits on their range of choices. It is important to examine whether student who read less than their peers would make different choices with access to different materials: non-fiction compared to fiction or Historical Fiction compared to Science Fiction. Would they become more engaged in their reading? Would it be more purposeful? Would their achievement levels increase?

The PIRLS results might indicate the need to address purposeful use. Some students find reading boring, or uninteresting, or applicable to their present lives. They may have an adequate base of skills and might be able to do better, but they do not see the importance of these kinds of tests. Do they have access to what, in their opinion, is purposeful material. One of the critical challenges facing all teacher-librarians is finding resources for those who do not or will not read. Skateboarding magazines and books and magazines about computer games are often of interest to some of these students in the author’s school.

Classroom teachers, supported by literacy experts, provide the sets of skills upon which students can master the reading process. Access, sharpened with purposeful use, is likely what turns potential into achievement. Instruction in a subject, in and of itself, is not enough. The many tens of thousands of Canadian adults who studied second languages, or math, in their elementary and secondary schools can attest to the challenges linked to maintaining skills once mastered.)

Those, now adults, motivated by purposeful use, and access to opportunity to practice their skills, maintain mastery. In reading: it’s about instruction, access and usage. Students need access to libraries and teacher librarians and make use of the material they find in libraries. With these they can maintain, and enhance, their critical literacy skills.

______________________________________________________

Bibliography

Bussiere, P., F. Cartwright, et al. (2001). Measuring up: The Performance of Canada’s Youth

in Reading, Mathematics and Science : OECD PISA Study : First Results for Canadians aged 15. Ottawa,

Statistics Canada: 93.

Mullis, I. V. S., M. O. Martin, et al. (2007). PIRLS 2006 International Report: IEA’s Progress in

International Reading Literacy Study in Primary Schools in 40 Countries. Chestnut Hill, MA, Lynch School

of Education - Boston College: 458.

References Cited

i

“It’s the economy, stupid!” Retrieved February 13, 2008 from:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/It's_the_economy,_stupid

ii Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) defines reading literacy as “Understanding, using and

reflecting on written texts, in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential, and to

participate in society” (Bussiere 2001 p. 10).

iii Canadian results were based on the participation of students in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and

Nova Scotia. In this case Nova Scotia achievement numbers were not reported and so the average was adjusted to

reflect the four remaining provinces.

______________________________________________________

Copyright ©2009 Canadian Association for School Libraries | Privacy Policy | Contact Us

ISSN 1710-8535 School Libraries in Canada Online