Supporting Literacy in Ethiopia through Libraries and Reading Rooms

Dr. Marlene Asselin

University of British Columbia

Marlene Asselin is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia. Her teaching and research interests are in literacy education, digital literacy, information literacy, and school library 2.0. She is a former President of the Canadian Association for School Libraries and of the Lower Mainland Council of the International Reading Association. She currently serves the International Association of School Librarianship as Regional Director for Canada and co-Chair of the International Development SIG.

Dr. Ray Doiron

University of Prince Edward Island

Ray Doiron is Professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Prince Edward Island and currently serves as Director of the UPEI Centre for Education Research. He teaches courses in early literacy and school librarianship and his research interests include digital literacies, social networking and school libraries. Ray is a Past President of the Canadian Association for School Libraries and now is co-Chair of the International Development SIG for the International Association of School Librarianship.

Issue Contents

______________________________________________________

For three weeks in November 2008, we joined a team of ten Canadians as part of a guided tour of the reading rooms of Ethiopia developed by CODE, a Canadian NGO that works with partners in 11 countries (http://www.codecan.org/). CODE Ethiopia, our host and key partner with CODE, has established 62 reading rooms in remote rural areas of Ethiopia and 20 more are opening. Our travel team consisted of people from a variety of professions and provinces thus creating a uniquely multi-perspective experience.

The challenges for improved education and literacy in an overwhelmingly rural country of over 80 million people, and growing, need to be contextualizd. Although it is difficult to get absolutely accurate statistics, the most recent data from UNICEF (2000- 2006) show the youth literacy rate at 42% and a gap between rates of males (62%) and females (38%). There are five major local languages with Amharic being dominant. Instruction is in the local language in primary school, and children begin to learn English in grade 3. English is the language of instruction in secondary and post-secondary schooling. Primary school enrolment has increased dramatically in the past five years with 68-78% (different data sources) of students reaching grade 5. However, enrolment in secondary school drops to 38% for males and 26% for girls.

Literacy and libraries have a fascinating and complicated history that needs to be considered as one explores the topic in Ethiopia. Historically, literacy was a tool used by feudal kings and Emperors through thousands of years of conflict. Literacy was important among the ruling classes, but not for the citizens that those in power controlled. The literate classes expanded as Ethiopia developed; however, reading remained a tool for education and work. Little focus was placed on reading for enjoyment. Then, in 1974 when the Derg military junta came to power following the ousting of Haile Selassie, national literacy programs were instituted with communist zeal. Libraries were placed around the country to support these programs. Libraries became associated with the repressive political movement. After the fall of the Derg in 1987 this association remained. It is from this point that today’s libraries and librarians in Ethiopia had to start working with communities to change the popular perception of a library as a propaganda machine towards one of libraries as useful and enjoyable spaces where people can learn and where the love of reading is promoted.

The Canadian CODE team visited six reading rooms and met the staff, children and library management team in each location. The communities are extremely proud of their reading rooms and are equal partners with CODE Ethiopia in their success through their local leadership roles in constructing the buildings to house the reading rooms, managing their operations and covering recurring costs. This high level of community investment is at the core of sustaining the library and any successful development project. Library staff are trained by CODE Ethiopia and collections are supplied by both CODE Ethiopia who draws support from CODE in Canada, CODE’s affiliate the International Book Bank, Book Aid International and other charitable organizations. We visited the CODE Ethiopia warehouse in Addis Ababa and learned about the management and delivery of books throughout the country. We were also privileged to meet CODE Ethiopia Director Ato Tesafaye Dubale, who shared his vision for libraries in Ethiopia which is grounded in developing literacy for elementary children and building in them a love for reading. It was truly inspiring to hear how hard he and his dedicated staff have been working to bring this vision alive. The warehouse is a modest space for such important work, stacked high with books in English that are donated from different parts of the Western world and all organized and ready for shipping to the local reading rooms. Many of the books are textbooks for language arts, science, and math with some supplementary reading materials in novels and picture books, both fiction and nonfiction.

An exciting part of our briefing was learning how CODE Ethiopia publishes over 300 titles of children’s books in four local languages. Everywhere we went we listened to children read these valuable books. These humble publications are rich with the voices of children, local storytellers and the extensive oral traditional tales of the 17 tribes in Ethiopia. Every reading room was full of young people reading, sitting or standing wherever they could including in stairwells and dark corners. Although each community has ambitions to expand their library collections, they are limited to print resources as computers and internet access is rare.

Our arrival at each reading room was greeted with elaborate and colorful singing and dancing by children from the communities. We heard the children sing, read their own poetry and speak of the importance of literacy, learning and reading. They have a great desire to learn, especially in the sciences, math and oral and written English. We were honored with the traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony and gifts of beautiful local crafts. These receptions were most overwhelming in such humble circumstances. Within the reading rooms, students of all ages were reading and working in their workbooks and our team sat with them to hear them read, talk about their school work, and learn about each other. One nine-year-old girl, whose lively reading of an Amharic folktale, kept us totally engaged even though we couldn’t understand the language!

Collections in the reading rooms reflected what we saw in the CODE Ethiopia distribution centre in Addis – a heavy emphasis on the donated subject curriculum texts (in English) and less on trade books. As well, a large collection of the story books and supplementary readers published by CODE-Ethiopia was there to fill the void within the western books. This gap in texts to support the curriculum poses a great challenge to teachers and students who rely on them as the only comprehensive resource to support the courses they teach. Teachers are further restricted by inadequate (or little to no) teacher training and by standardized tests that students are compelled to pass to move ahead. There is little time or place for individual thinking or creativity. Teachers are thus doubly limited – in both opportunities to learn more about teaching practice and in available resources of many kinds. A greater understanding of how library programs could benefit both students and teachers will continue to develop within local institutions that strengthen literacy and promote a more literate environment.

As the only literacy and library researchers in the group, we wanted to gain as broad a picture of libraries in Ethiopia in our short time there. We arranged additional visits to public and school libraries in the northern part of the country and in the Addis Ababa area, as well as to the impressive new National Archives and Library of Ethiopia (NALE) in Addis Ababa. Also in Addis Ababa, we visited the Shola Children’s Library (started by Ethiopia Reads-- http://www.ethiopiareads.org/index.htm) which runs similar services to CODE Ethiopia but in urban settings. The Ethiopia Reads group also has started to support 20 school libraries and we were able to visit one of these urban school libraries. We were impressed with the Shola Children’s Library as a vibrant central children’s library (which runs Saturday morning story times and also has a sanitation center for children to bathe and have their clothes washed). The collection was more balanced between text and trade books and it ‘felt’ like a children’s library we might see in North America. This is likely due to their strong and generous sponsorship by library and literacy associations in the U.S. Their publication program of books in English and Amharic is notable with Jane Kurtz as one of their principal authors and a system in place to support Ethiopian illustrators for their books. Coincidentally, the Director of Ethiopia Reads, Ato Yohannes Gebregeorgis, had just been nominated for the CNN Hero of the Year and was in the U.S. touring so we missed meeting him. However, his young, techno-savvy and dynamic staff guided us through the entire site including the publication “centre.”

At the end of our trip, we visited two international schools in Addis Ababa. The timing was significant as we had been trying to learn about and understand libraries in an Ethiopian context. Then we were suddenly faced with Western style institutions in the midst of Ethiopia. The libraries in these schools were staffed by a qualified, full-time librarian and an extensive support staff (often volunteer). Collections and the physical space were grandiose in our new view; we could have been in any exemplary school library in Canada. It is contrastive experiences like these so close together that helped us understand how precious learning resources are and how critical access to these resources is for literacy development for individuals and their communities.

We also visited two major universities (Addis Ababa and Bihar Dar) where we met with Deans of Education and University Librarians. With the increased attendance of school age children over the last few years (UNESCO’s Education for All), the challenge of training teachers--both new and practicing teachers-- is on a scale we couldn’t imagine. Like the schools we visited, the university facilities (both library and instructional) were limited in the number of resources and services they were able to provide.We were struck by how wonderful it would be if the pre-service teachers in these universities could learn firsthand about CODE-Ethiopia’s reading rooms and ways of promoting reading but resources are so scarce for these dreams. We found the university librarians held remarkably progressive visions in the face of great obstacles including dramatic annual increases of numbers of students attending university, library staff with no training, the use of card catalogues, and poor Internet access. The academic libraries are open 22 – 24 hours per day to serve the high needs for information access by students and faculty.

We kept getting the feeling over and over again that many of the library personnel just needed to ‘see’ models of how libraries can and do work in other countries. They sense something is not right about the current situation and feel just more books would solve the problem. We discussed with CODE-Ethiopia the possibility of establishing model reading rooms at universities where pre-service teachers are being trained so that they will get to use a reading room for their teacher preparation, but more importantly, they will go out to the school system understanding how libraries play such a major role in literacy achievement. As we reflect on our experiences we wonder if the reality is that the real barriers may be in the vision and understanding of the roles that libraries play in learning and literacy and the need to be exposed to other visions. In this sense the history of libraries in the Ethiopian context proves to be a continuous challenge.

In addition to all the reading rooms, libraries and schools we visited, we also experienced amazing natural, historical, and cultural sites including a heart-stopping drive through the immense Blue Nile Canyon, the churches of Lalibella in the north that are literally carved out a mountain of solid rock from the top down, ancient monasteries on remote islands, traditional Ethiopian food and music highlighted by several lively performances of traditional shoulder dancing. It has to be seen to be believed!

In spite of living subsistence lives and struggling with many obstacles to progress, we found people to have remarkably positive outlooks on the future of their country and a strong and able population of young adults eager to step into leadership positions. While so many of the young people we met will always be vivid memories, two images remain vivid and powerful. A young father in Lalibela spoke eloquently and passionately about his nearly completed master’s thesis which focuses on gender differences in learning science. His research design involved a large sample of students, teachers and parents, and multiple methods of data collection. He is committed to addressing the issue of differential treatment of girls in homes and schools that his study revealed. The other young person worked as a museum tour guide in Addis Abbaba and we were amazed to learn that his newly completed Masters degree in education was one of the first to address multiculturalism and multilingualism in Ethiopian schools. He was very excited to learn we were Canadian as one of his major sources of his own learning was a Canadian scholar. Both these young people face immense challenges in implementing implications of findings from their studies in ways far beyond what we can imagine. But they are fully committed to supporting their country towards modernization while maintaining the strengths of their unique place in the world – the cradle of civilization.

______________________________________________________

Pictures from Ethiopia

International School Library |

Librarian in rural Ethiopia |

Shola School Library |

Reading Room Children |

Librarians at Durbete Reading Room |

Library at Lalibella School |

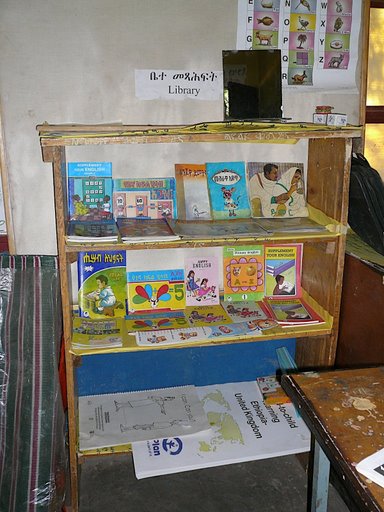

Library Sign in Rural Ethiopia |

Librarian at Lalibella School |

______________________________________________________

Copyright ©2009 Canadian Association for School Libraries | Privacy Policy | Contact Us

ISSN 1710-8535 School Libraries in Canada Online